I’m a proud “friend of Ethel”!

What is she talking about, you might ask. Well, in times gone by, the phrase “friend of Dorothy” – nudge nudge, wink wink – was commonly used amongst gay men to surreptitiously identify themselves as gay. So, a musician friend and I came up with “friend of Ethel” as the perfect euphemism for a gay woman, referring to the brilliant and defiant Ethel Smyth ; an English composer, suffragette and open lesbian who lived between 1858 and 1944.

Have you heard of her? You’d be forgiven if this is the first time you’re reading her name. I’m a professional musician, feminist, and lesbian and even I didn’t know she existed until a year ago. Something’s gone wrong there, right? So, other than trying to make “Friend of Ethel” happen, here I begin an exploration of why LGBT History Month is important, and consider whether we need to do more in the musical world to champion composers and performers with an LGBT+ identity.

“We are here and always have been”

I asked Richard Goalen, a violinist in the London Gay Symphony Orchestra, whether he thinks it’s important that we tell the stories of LGBT composers. He said, “Even if the composers are famous it’s not always common knowledge that they might have been LGBT, so I think it helps build into people’s consciousness that we are here and always have been”.

He added “Having grown up in the sixties and seventies I’m well aware of the struggle that we had to be accepted, and I think it’s important that these memories are kept alive so we don’t return to those days. History of any kind is important, otherwise hard-won freedoms can easily be lost.” As being gay was still illegal in the UK until 1967, and still officially classed as a mental illness by the World Health Organisation until 1973, it’s easy to see why it’s important to LGBT+ people that even their recent history isn’t forgotten.

“It’s important that these memories are kept alive.”

On the subject of history, I would love to tell you more about Ethel Smyth. Ethel wrote her story down in various memoirs and, contrary to what we might think about women born in the 1800s, she wrote honestly about her attraction to women. As a young woman, she studied composition in Leipzig with Heinrich von Herzogenberg, where she developed feelings for his wife, Lisl. She writes: “If I ever worshipped a being on Earth it was Lisl.”

Ethel also had a passionate affair with Mary Benson (“Ben”), wife of the then Archbishop of Canterbury. She wrote in a letter to Ben, “The reasons for which I love you are unshakeable. Here are some of them; your fire, your intensity, your power of sustained effort, your extraordinary grip over other souls, your intellect, and, above all, in the words of a prayer I like, ‘your unconquerable heart.’” Later in her life she developed feelings for both Emmeline Pankhurst and Virginia Woolf.

You might ask at this point “Does it matter though?” Yes, I believe it does. “Isn’t a person’s sexuality irrelevant?” you might ask. Well no, it really isn’t. Ethel’s sexuality was a part of her, and I’m sure it was very important to her. We must remember that she lived in a time when same-sex attraction was considered unnatural, and was not accepted as a valid life choice, so to act on her feelings would have been bold. This gives us a sense of the kind of person she was.

I also imagine the feelings Ethel had for women will have influenced her compositions. I challenge any composer to go through their musical output and not find a single piece written about someone they loved.

Ethel’s compositional output included chamber music, orchestral works, and operas, including The Wreckers, which is being performed at Glyndebourne this year. As a cellist, I am thrilled that she wrote two cello sonatas. Here is the first movement of her opus 5 cello sonata.

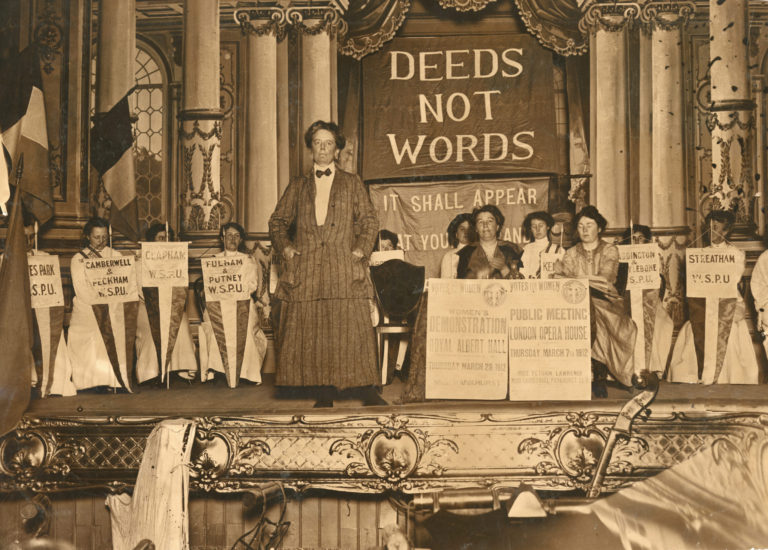

In the early 1900s, Ethel joined the Women’s Social and Political Union, the more direct of the two suffragette organisations crusading for women’s votes. She composed their anthem, March of the Women.

At one stage, she was involved in smashing the windows of MPs who opposed votes for women. She was put in prison for doing this, but this didn’t seem to unnerve her. It has been widely reported that on one occasion she was seen leaning out of her cell window and leading a choir of suffragettes in the singing of the suffragette anthem, conducting the women with her toothbrush!

It is important that stories like this are remembered and told. If nothing else, they remind us that LGBTQI+ people have played a pivotal role in some of our most important historical moments.

“LGBTQ folks may have felt and feel it’s necessary to hide or deny themselves”

I wanted to get a picture of what LGBT+ representation looks like in the jazz world, so I asked Charlotte Keeffe, a jazz trumpeter, composer and improviser, and a gay woman. She said that “performing music by LGBTQ composers creates a connection, an openness, an invitation to all – freedom.”

“LGBTQ folks may have felt, and feel, it’s necessary to hide or deny themselves, for fear of not being accepted by society” but Charlotte now feels she can openly talk about her girlfriend, Lara De Belder, on stage when discussing the pieces she has written for and about her.

Charlotte and Lara met in the London Gay Big Band, which has performed in many Pride festivals around the world. She said, “Picture a full-on LGBTQ swinging big band with beautiful LGBTQ singers fronting the band.” She told me that they have performed in front of the famous Brandenburg gate in Berlin, saying, “It’s moments like that that are amazing to think how far we’ve come since the World Wars and Hitler.”

Charlotte proudly led an all women line-up of the London Gay Big Band in an LGBT+ jazz night last year. “The energy was electric, it was such a vibrant evening – full of glitter too,” she described, adding, “there are lots of LGBTQ concerts and musical celebrations happening in the jazz world, but of course this is not the case everywhere”.

Here is Charlotte playing with her jazz quartet:

Charlotte is part of a new online music series called Stranger Fruit, celebrating lesser-known women in jazz.

She told me: “I’ve chosen to shout out about trumpeter Ernestine ‘Tiny’ Davis, and yes, I will be talking about how she lived with her same-sex partner and how they grew old together running a bar/club, becoming LGBTQ icons.”

I got the impression from talking to Charlotte that there was an element of catharsis in being able to shout out about her own sexuality. This is definitely something I can relate to. Charlotte is close to me in age, and therefore went to school during the time that Margaret Thatcher’s egregious Section 28 was in force.

Section 28 was a clause in the Local Government Act (1988) which stated: “A local authority shall not intentionally promote homosexuality or publish material with the intention of promoting homosexuality, or promote the teaching in any maintained school of the acceptability of homosexuality as a pretended family relationship”.

At a time when there had been some progress in the rights of LGBT+ people, it was illegal for a school teacher to talk about LGBT+ history, or to even educate children about LGBT+ issues or rights. For this reason, the subject of LGBT+ people didn’t come up in class throughout my whole time at school.

Growing up lesbian in this environment was like being permanently gaslit; the silence on the subject was deafening, and since teachers and other authority figures didn’t mention the LGBT+ community, I assumed that gay people were very rare, and possibly not even good people.

Section 28 was ended in Scotland in 2000 and elsewhere in the UK in 2003, but it had already done much damage to the lives of young LGBT+ people. I know that it would have made a difference to me growing up if sexuality and gender had been discussed openly, and it would have been reassuring to know that many LGBT+ musicians had come before me.

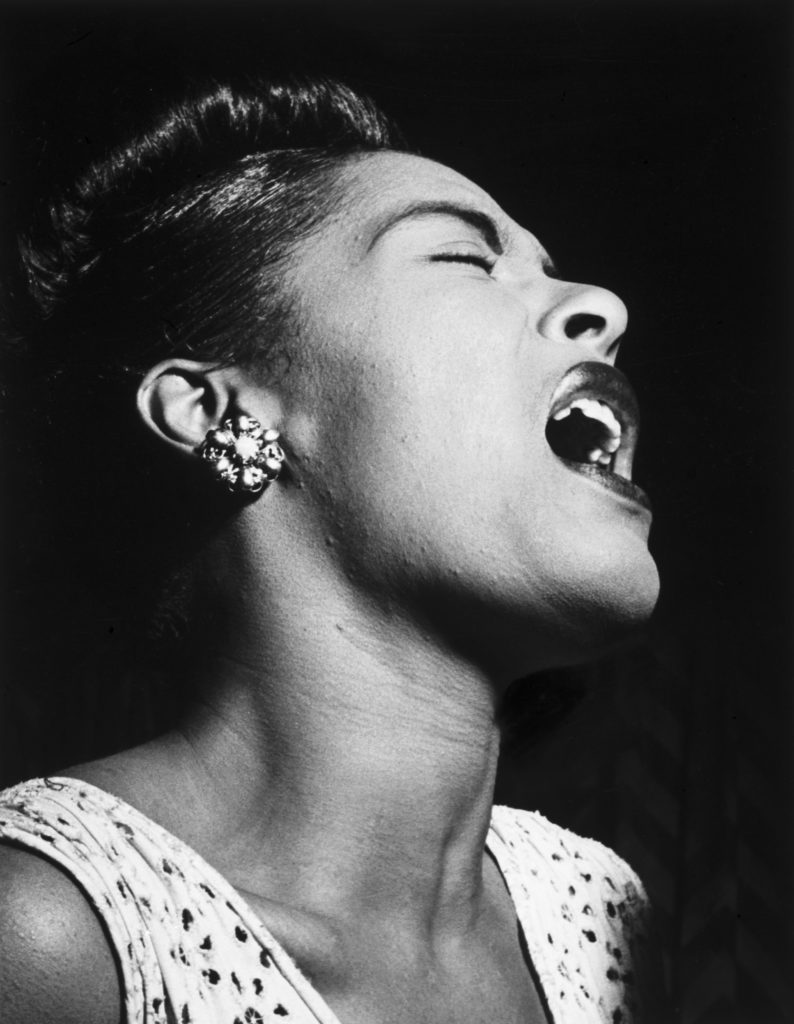

It is amazing – almost therapeutic – to now discover that across the centuries there have been musicians of all kinds who are LGBT+, from Sappho (who in around 600BC wrote amorous poetry about women to be accompanied by the lyre), to 20th Century figures like Billie Holliday, who was openly bisexual. Many of our well-loved classical composers were LGBT+: Jean-Baptiste Lully, Aaron Copland, Samuel Barber, Francis Poulenc, Ivor Novello, and Benjamin Britten to name a few.

“But why does this matter?” I hear you shout. It matters because representation is everything. It’s the difference between feeling like you’re the only one, and seeing yourself reflected in others’ stories. It is so vital that music reflects the full diversity of the world we live in. When there is so much diversity locked up in musical history, in untold or edited stories, I believe it is our job to share these accounts without omissions now. It is right to celebrate everything about these composers and to allow them to come out, even if they weren’t able to in their lifetimes.

One woman who felt the need to keep her head down at times was Angela Morley (1924-2009). She was a composer and arranger, and if you’ve seen Star Wars, ET, Home Alone or Schindler’s List you will have heard music orchestrated by her. Angela was a transgender woman. This means that although she was declared to be male when she was born, she knew herself to be a woman. She struggled with her gender identity throughout her life, but it wasn’t until the 1970s that she felt able to publicly live as a woman.

Throughout the 70s and 80s Angela lived in LA, composing and arranging music for TV and film. She collaborated with Warner Bros, Paramount Pictures, Universal Pictures, and 20th Century Fox, and worked alongside John Williams and the Boston Pops Orchestra on many projects. Angela is also known for composing the soundtrack for the animated film Watership Down.

Despite her success, Angela would often turn down TV appearances because she worried about how she might be received. She has frequently been misgendered or referred to by her old name, known as dead-naming, in writings about her life. Trans people today will know only too well how unsettling and distressing it is to be called by the wrong name or gender pronouns. So I’m taking this opportunity to state that the respectful thing to do when writing about the history of a trans person is to call them by their chosen name and pronouns, even when referring to something that they did in the past.

Towards the end of Angela’s life she dedicated more time to instrumental compositions, writing for the saxophone (her own instrument), the cello, and the violin. Here is her beautiful Reverie for violin:

Sadly, the trans community today is subject to extreme prejudice, disrespect and cruelty. I believe that misinformation and lack of education are huge factors in this. Certain media outlets seek to imply that trans people are a new phenomenon, or a fad, while this is completely untrue. In fact, much trans history has been deliberately erased.

For example, in 1933 the Nazis burnt 20,000 books and papers from the Institut für Sexualwissenschaft (Sexology Institute) in Germany. The medical records and personal stories of transgender people, as well as research into gender variance and gender-affirming surgical procedures was all lost, never to be replaced.

We cannot undo the cruel things that have been done to the LGBT+ community, but we can change things for the future. By platforming trans composers or performers (not just in LGBT History Month), we can share a new message: “You are welcome. We want to hear your voice”.

I spoke to Jordan Williams, a Welsh folk musician with Live Music Now and the cellist in folk trio Vrï, to discover whether the voices of LGBT+ people can be found in the British folk songs of the past.

“LGBTQ+ people are underrepresented in the traditional music scene.”

Jordan is gay himself but said he wasn’t aware of many clear references to LGBT+ people in the traditional songs. He also feels that LGBT+ people are underrepresented in the traditional music scene. However, he did point me in the direction of queer folk musicians Sophie Crawford and George Sansome, who have been researching the representation of LGBTIA people in traditional folk songs by delving into the archives at the Cecil Sharp House and the Vaughan Williams Memorial Library. They were surprised to find at least 70 songs that contained at least some sort of LGBTQIA reference, including references to gender bending and same-sex desire.

You can read more about their findings here.

Jordan told me that in contemporary folk, there are an increasing number of musicians who identify as LGBTQ+ who are creating their own folk songs and dance tunes which reflect these aspects of their identity. He said “LGBTQ+ people have always been present in our communities,” and said that we have a chance to change the narrative: “The preservation and incorporation of LGBTQ+ stories deserve to be as much a part of our traditional music as any other community in society.”

Jordan himself has written new folk songs about Welsh LGBTQ+ history, taking as his themes the poet Edward Prosser Rhys, the historian Jan Morris and the AIDS crisis. In his song below, the words talk about how boys with AIDS apologised to their mams for being gay, for having AIDS and for dying.

Jordan concluded that whilst people within the LGBTQ+ community can share LGBTQ+ stories through their music, “It is the job of everyone outside that community to listen, engage and understand to the best of their abilities.”

I agree with Jordan here. History may have been unkind to us queer folk, but we can look ahead, and change the narrative. By telling LGBT+ history in all its forms, we can open up dialogues, increase visibility and dispel myths and stereotypes. And with every LGBT+ musician that we platform, we are undoing the wrongs of the past, and creating the world we want to see; one where everyone can live openly and without shame, regardless of their sexuality and gender; one where we don’t criticize or judge but seek to understand; and one where we celebrate the diversity of humanity and revel in its creativity.